This week marks the beginning of formal talks to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, an agreement President Donald Trump has called the “worst deal in history.” To make it a better deal, his Administration released a set of negotiating objectives last month, but they ignored the most outrageous example of how American consumers are “losers” under NAFTA.

Literally losers. When it comes to country-of-origin labeling (COOL) on meat, American consumers are in the dark, and we have Canada and Mexico to blame.

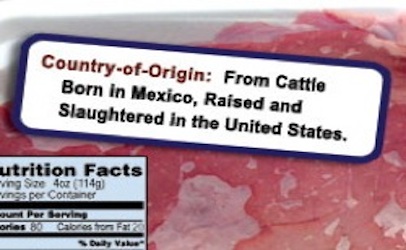

Until 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture required retailers to label fresh beef and pork “muscle-cuts” — think steaks and pork chops — with country-of-origin information, specifically where the cow or pig was born, raised and slaughtered. Canada and Mexico sued, however, and an international tribunal at the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled that the labeling regulations were an unlawful trade barrier. Faced with sanctions, Congress folded, and consumers lost their right to country-of-origin labeling on beef and pork.

Until 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture required retailers to label fresh beef and pork “muscle-cuts” — think steaks and pork chops — with country-of-origin information, specifically where the cow or pig was born, raised and slaughtered. Canada and Mexico sued, however, and an international tribunal at the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled that the labeling regulations were an unlawful trade barrier. Faced with sanctions, Congress folded, and consumers lost their right to country-of-origin labeling on beef and pork.

A new NAFTA could undo the effect of the WTO’s decision. Yet remarkably, the office of the U.S. Trade Representative has no plans to salvage Americans’ right to decide for ourselves how meat is labeled in this country. Is this what “America First” is supposed to look like?

Never before has there been such an explicit example of an international trade body nullifying a U.S. law, and a popular law to boot. Poll after poll has shown that the vast majority of Americans — 89 percent in a survey commissioned by Consumer Federation of America last month — want labels telling them were their meat comes from. Why should trade rules prevent Americans from knowing where their food comes from?

President Trump owes American consumers an explanation. This comes at the same time that his Administration is working to open U.S. borders to more foreign-origin meat, including a proposal to authorize chicken imports from China, where health officials are scrambling to contain the latest bird flu strain and rampant overuse of antibiotics has created superbugs resistant to drugs once thought of as a last resort.

More than ever before, consumers are right to demand country-of-origin labeling. If members of Congress think consumers don’t have a right to this labeling, or that it’s too expensive for big meat processing corporations to have to keep track of where animals are from, they can explain that to the voters. But Americans’ elected officials, not an international trade tribunal, should make that decision.

This is not the trade policy that Trump promised in his campaign. He pledged to withdraw the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership because the deal “will undermine our independence.” He opposed that deal because it “creates a new international commission that makes decisions the American people can’t veto, making it easier for our trading competitors to ship cheap subsidized goods into U.S. markets.”

But our trade deals already let international commissions make decisions the American people can’t veto, and consumers are paying the price.

But our trade deals already let international commissions make decisions the American people can’t veto, and consumers are paying the price.

Country-of-origin labeling on meat isn’t about protectionism. Giving consumers origin information supports many different, legitimate goals, from sustainability to food safety. That’s why a federal appeals court threw out a lawsuit that the big meatpackers filed to get rid of the regulations. Among the reasons that swayed the court was the fact that the federal government has required country-of-origin labeling on all kinds of foods for more than a hundred years.

As the Administration renegotiates NAFTA, it should require a fix to country-of-origin labeling. Americans want to know “Where’s the beef — from!” And they have every right to know.

About the author: Thomas Gremillion oversees the research, analysis and advocacy for the Consumer Federation of America’s food policy activities. He also monitors food safety activities at USDA, FDA and in Congress, where he advocates for strong food safety protections for consumers. Prior to joining CFA in 2015, Gremillion practiced environmental law at Georgetown University Law Center’s Institute for Public Representation, where he represented community groups and advocacy organizations in litigation against polluters and government regulators. He also served as an associate attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center in Chapel Hill, NC, where he specialized in transportation and land use issues. Gremillion is a graduate of Harvard Law School. He graduated magna cum laude from the University of South Carolina with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)