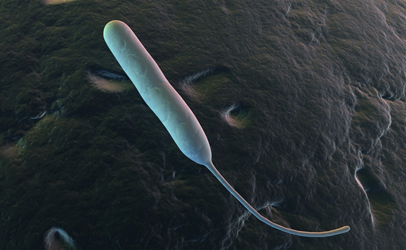

The liquid that comes off of a defrosting chicken provides a safe harbor for Campylobacter, according to a new study. Chicken “juice” from a defrosted bird turns a surface into a protein-rich environment in which Campylobacter can form a protective biofilm, reported a study from the Institute of Food Research. This biofilm helps bacteria attach to things and survive tough conditions. The researchers used strains of Campylobacter jejuni, the form of the bacteria that causes 90 percent of Campylobacter foodborne illness infections, for the study. While all Campylobacter usually has trouble living outside its natural environment, a chicken’s gut, chicken juice turns a formerly unfriendly surface into one that attracts Camplyobacter biofilm, found the researchers. “This film…makes it much easier for the Campylobacter bacteria to attach to the surface, and it provides them with an additional rich food source,” said Helen Brown, a PhD student at IFR, funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. Brown’s studentship is co-funded by Campden BRI, in a statement. While other types of molecules from animals, such as bovine serum proteins or milk, either slow or inhibit biofilm formation, the liquid expelled by chicken enhances it, according to the paper. “This study highlights the importance of thorough cleaning of food preparation surfaces to limit the potential of bacteria to form biofilms,” said Brown. Researchers designed the experiment to imitate conditions in an industrial kitchen, putting chicken juice on stainless steel surfaces. While the presence of chicken broth increased Campylobacter attachment and growth, the concentration of chicken broth didn’t make a difference. More concentrated broth did not help Campylobacter biofilm to attach and grow. Chicken broth also evened the playing field for different strains of Campylobacter. Strains that have no flagella, or tail, usually attach to surfaces and form biofilms more easily, but chicken broth made it easier for strains without flagella to attach to surfaces too, according to the study. The researchers said their findings point to a need for more research on animal juices and bacteria. “This highlights the need for future studies to not only investigate the link between chicken or pork soil and surface conditioning but also assess the effect of other meat exudates on biofilm formation,” reads the paper’s conclusion. The study was published ahead of print Sept. 5 in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

The liquid that comes off of a defrosting chicken provides a safe harbor for Campylobacter, according to a new study. Chicken “juice” from a defrosted bird turns a surface into a protein-rich environment in which Campylobacter can form a protective biofilm, reported a study from the Institute of Food Research. This biofilm helps bacteria attach to things and survive tough conditions. The researchers used strains of Campylobacter jejuni, the form of the bacteria that causes 90 percent of Campylobacter foodborne illness infections, for the study. While all Campylobacter usually has trouble living outside its natural environment, a chicken’s gut, chicken juice turns a formerly unfriendly surface into one that attracts Camplyobacter biofilm, found the researchers. “This film…makes it much easier for the Campylobacter bacteria to attach to the surface, and it provides them with an additional rich food source,” said Helen Brown, a PhD student at IFR, funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. Brown’s studentship is co-funded by Campden BRI, in a statement. While other types of molecules from animals, such as bovine serum proteins or milk, either slow or inhibit biofilm formation, the liquid expelled by chicken enhances it, according to the paper. “This study highlights the importance of thorough cleaning of food preparation surfaces to limit the potential of bacteria to form biofilms,” said Brown. Researchers designed the experiment to imitate conditions in an industrial kitchen, putting chicken juice on stainless steel surfaces. While the presence of chicken broth increased Campylobacter attachment and growth, the concentration of chicken broth didn’t make a difference. More concentrated broth did not help Campylobacter biofilm to attach and grow. Chicken broth also evened the playing field for different strains of Campylobacter. Strains that have no flagella, or tail, usually attach to surfaces and form biofilms more easily, but chicken broth made it easier for strains without flagella to attach to surfaces too, according to the study. The researchers said their findings point to a need for more research on animal juices and bacteria. “This highlights the need for future studies to not only investigate the link between chicken or pork soil and surface conditioning but also assess the effect of other meat exudates on biofilm formation,” reads the paper’s conclusion. The study was published ahead of print Sept. 5 in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

Sponsored by Marler Clark