Editor’s note: This article was originally posted on FDA’s Consumer Updates page. A person commits a crime, and the detective uses DNA evidence collected from the crime scene to track the criminal down. An outbreak of foodborne illness makes people sick, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uses DNA evidence to track down the bacteria that caused it.

- determine which illnesses are part of an outbreak and which are not;

- determine which ingredient in a multi-ingredient food is responsible for the outbreak;

- differentiate sources of contamination, even within the same outbreak; and

- link small numbers of illnesses, including geographically diverse illnesses occurring across multiple states, that might not otherwise have been identified as a common outbreak.

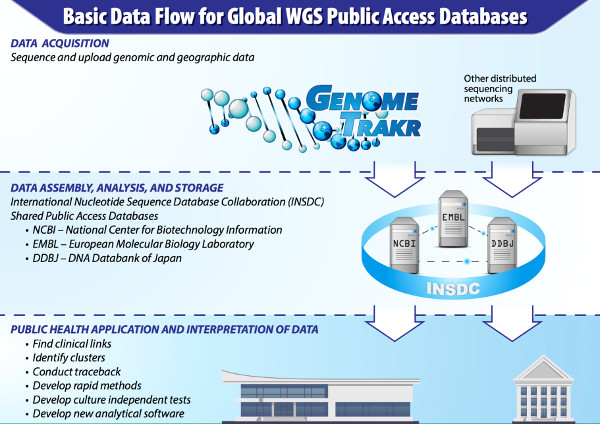

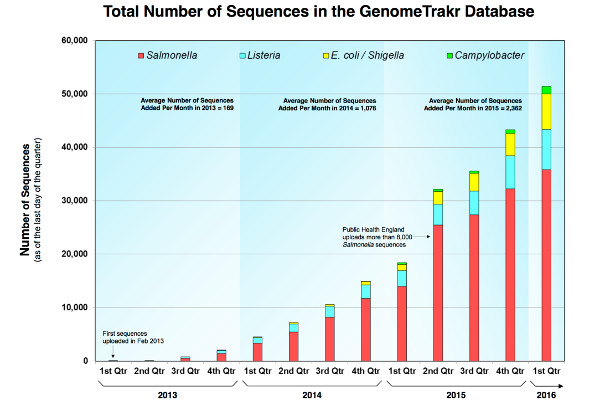

Once a bacterium is sequenced, the generic information can be used indefinitely. The “evidence” doesn’t get used up, and scientists can continue to match strains from years past. Brown says the FDA is pushing the whole genome sequencing technology out to the frontlines of food safety “as quickly and completely as it can.” What does this mean for future tracking of food-borne illnesses? Industry is starting to recognize and use whole genome sequencing as a way to monitor ingredient supplies, determine the effectiveness of preventive and sanitary controls, and determine the persistence of pathogens within the factory environment, Brown says. If a food production facility finds a pathogen during testing, it can use the GenomeTrakr database to help identify the source of bacterial contamination and take whatever corrective steps are necessary to make sure the food it produces is safe to eat. Allard adds that the FDA is working with like-minded food industry specialists who are examining the value of whole genome sequencing for food safety as they work to produce the safest food possible. “We’re helping to raise the bar for food safety around the world,” Brown says. (To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)