Editor’s note: This column by FDA’s Steven Musser and Eric L. Stevens was originally published on the agency’s blog.

FDA is laying the foundation for the use of whole genome sequencing (WGS) to protect consumers from foodborne illness in countries all over the world.

We recently traveled to Geneva to join a meeting of the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an international organization that works to protect consumer health and promote fair practices in food trade. There, we participated in a panel discussion on how best to share WGS globally to fight foodborne illnesses and elicit support from the world’s governments in this effort.

There’s no time to waste.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that as many as 600 million people in the world fall ill every year after eating contaminated food and 420,000 of these people die.

FDA has been a leader in the use of WGS to identify the nature and source of bacteria that contaminate food and cause outbreaks of foodborne disease. By sequencing the chemical building blocks that make up the DNA of these pathogens, WGS reveals their genetic fingerprint, offering clues about their geographic source, antimicrobial resistance, and other key markers that help scientists respond more effectively to food contamination, preventing illnesses.

In the last few years, WGS has fundamentally changed the way that we detect, identify and monitor microbiological food safety hazards within the United States. This technology is rapid, precise, cost-effective, easy-to-use, and can be applied universally to all foodborne pathogens.

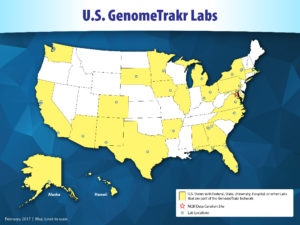

The GenomeTrakr is an international network of laboratories sequencing microbial foodborne pathogens and uploading the data to a common public database in real time.

The goal of GenomeTrakr is simple: to assemble a large, freely accessible database of genetic sequence information and accompanying metadata, e.g. geographic location and date, from food, environmental and human clinical isolates of bacterial pathogens. This information can be used by scientists on the trail of disease-causing bacteria, unmasking each contaminant’s identity and offering clues to where and how it got into the food supply.

Recently, public health institutions, including FDA, WHO and FAO (the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), have been working to raise awareness about the importance of WGS and the benefits of sharing both sequence information and metadata.

In Geneva we talked about how this technology is being utilized in some countries to support their foodborne disease surveillance system or outbreak investigation activities. We all understand that food is a global commodity, with complex shipping and distribution networks that can easily result in contaminated food being sold in more than one country. Thus, the most effective use of WGS in foodborne disease surveillance requires coordination and collaboration, and the panel emphasized the global health benefit of every country sharing their data. One approach would be sharing the data through FDA’s GenomeTrakr.

We are certain that the public health benefit of WGS will only become more evident with every foodborne pathogen’s genomic sequence that is shared. Already, GenomeTrakr has collected more than 142,000 sequenced strains, has made them freely available to anyone in the world, and continues to demonstrate how a large database of this kind is being used effectively for food safety within the United States, and throughout the world.

As the food supply becomes increasingly global, the use of WGS in a way that crosses national borders will ultimately help keep us all safe from foodborne illness.

About the authors: Steven Musser, Ph.D., is the Deputy Director for Scientific Operations in FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). Eric L. Stevens, Ph.D., is a Staff Fellow in FDA’s Division of Microbiology at CFSAN.

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)