Opinion

I am a trial lawyer who has for the last 30 years built a practice on food pathogens. Since the Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak in 1993, I have represented thousands of families who were devastated for doing what we all do every day – eat food. In those 30 years a variety of members of the food industry have paid my clients over $900,000,000.

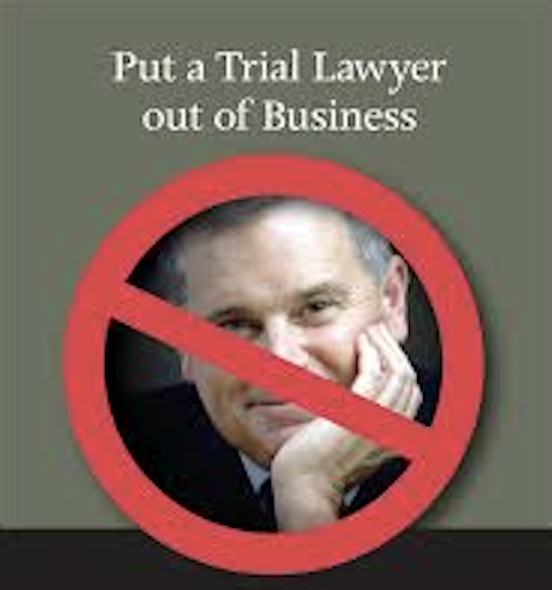

This may prompt some to consider me a blood-sucking ambulance chaser who exploits other people’s personal tragedies for personal gain. If that is the case, here is my plea:

Put me out of business, please!

For this trial lawyer, E. coli, Salmonella, Listeria, and other pathogens have made a far too successful practice – and a heart-breaking one. I am tired of visiting with horribly sick kids who did not have to be sick in the first place. I am outraged with a government and food industry that allow these poisons to reach consumers.

So, stop making kids sick and I will happily retire.

The FDA is at a crossroads. Over 10 years after the passage of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the goals of the most significant food safety legislation in decades have remained unfulfilled. As well-stated recently by Senator Durbin (D-Il) and Congressmember DeLauro (C-CT):

FDA is responsible for the oversight of nearly 80 percent of food in the United States. Too often, however, FDA has failed to protect Americans from dangerous food pathogens and outbreaks. Every year, more than 48 million Americans are sickened, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 lose their lives because of some bacteria or virus in their food. In 2011, FMSA was signed into law to transform the United States’ approach to foodborne illnesses. FSMA requested FDA to be more proactive, not reactive, to foodborne illnesses to prevent outbreaks in the first place. FSMA empowered FDA with new authorities, resources, and funding to accomplish this goal. But, as outlined in the Reagan-Udall report, FDA has not made this shift, despite FSMA’s passage more than a decade ago. FSMA required FDA to promulgate several rules so that it would prevent rather than respond to foodborne outbreaks. However, more than a handful of times, FDA missed congressionally mandated deadlines to implement them. FSMA also required FDA to “increase the frequency of inspection of all [food] facilities,” to ensure companies’ compliance with safety and quality standards. But FDA inspections have plummeted since FSMA was signed into law.

The FDA was, and for good reason, embarrassed by the likely illnesses of infants who became sick after consuming formula produced in a manufacturing plant that seemed to care little about the safety of its product. The FDA failed to properly inspect the plant which then led to formula shortages that still threaten infants today. For good reason FDA Commissioner Califf asked the Reagan-Udall Foundation expert panel to suggest fixes to the FDA.

Mr. President, Mr. HHS Secretary and FDA Commissioner please listen to those experts. Those experts were clear that the current structure at FDA needs change to make food safer. In its final report the Reagan-Udall Foundation panel in part recommended:

Given the economic impact that foodborne illness and diet-related chronic disease have on Americans and the federal budget, it is imperative that the Human Foods Program [which includes both food safety and nutrition] become more prominent. When compared to the medical products programs within FDA, the Human Foods Program continuously struggles for visibility and prominence. A component of this elevation of the Human Foods Program is strong advocacy to advance the Human Foods Program at all levels of the government, especially at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the White House, including the Office of Management and Budget.

- The Human Foods Program should have clear lines of authority.

- Within the Human Foods Program, the importance of nutrition should be elevated.

- The foods portfolio of ORA [inspections] should be integrated directly with the other elements of FDA’s Human Foods Program.

- The food-relevant work of CVM [animal food] should be integrated with the overall FDA Human Foods Program.

- A new Foods Advisory Committee, at the Commissioner-level, should be established to strengthen external input to Human Foods Program activities.

My vision, perhaps a bit more aggressive, is of a more empowered food-side of the FDA that would create two Senate appointed Commissioners – one with a portfolio of all aspects of food (food safety and nutrition) as mentioned above, and one with a portfolio of drugs and medical devices.

The time for half measures is past. It is time to be bold. It is time to move the FDA from reactive to proactive. It is time to do what needs to be done to bend the curve in the numbers of those negatively impacted by the food they consume.

Progress in the safety of our food supply can be made and history can be a guide.

When the Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak happened in 1993 several hundred were sickened, many severely, with at least four dead, from eating a hamburger. It was the first crisis of the Clinton Administration and the USDA/FSIS. The meat and restaurant industries were facing the ire of an angry public. Many thought the problem insoluble. Yet, the industry, government and consumers came together to find a way to lower E. coli in hamburger and to drive the numbers of ill down.

It worked. For years E. coli in hamburger was my firm’s “bread and butter.” In time the numbers of people sickened by E. coli in hamburger continued to fall to a point that, with government help, the meat industry met my challenge to: Put me out of business, please!

It is now time for the FDA to be reformed enough that the successes of the USDA/FSIS in the 1990’s can be replicated today. The time is long past for the FDA to: Put me out of business, please!

Mr. President, Mr. HHS Secretary and FDA Commissioner please listen.